It is curious to see how our attitude towards life changes (for the worse) as we grow up. We are all born optimists. But at some point in the journey, that optimism turns into pessimism.

When I was a five or six-year-old child, I had a business plan that I considered infallible.

Imagine being a little girl in a house where, many nights, there was nothing but an apple to eat. I still have the picture engraved in my heart: my parents unconditionally gave me the apple, and they drank a cup of tea with a piece of bread.

Yes, as a child, things were not accessible at home. In addition to the financial needs, two tragic accidents suffered by my father forced me to grow up suddenly. My childhood evaporated before my eyes, no questions asked.

A combination of survival instinct, entrepreneurial mindset, and the desire to offer my parents a solution to our problems must have been the starting point for the business plan that I believed would save us.

The plan didn’t require a considerable investment, which made it a bargain. It involved buying one US American dollar. Yes, in my kindergarten economist estimations, one dollar would make us millionaires (well, that happens when you are born in a country where the currency is worthless and the word “dollar” is magic music to your ears, the highest icon of the American dream).

I remember pitching my plan to my parents, selling the idea with conviction. However, I cannot remember their reaction or response. While the latter seems like a random observation, it’s essential to the story I want to share.

As I tell you, my family’s situation was far from ideal. Writing about it now, I realise it was worse than it seemed to me then.

That dollar was, in my mind, our lifeline. But my parents never bought that dollar. At that moment, I should have figured out that the plan was not as good as I thought or that I needed to be a better salesperson to convince them to be my partners. Even today, when I look back on that plan, I think it would have saved us. My inner child still believes that.

Why am I telling you this story? Why does it still move me to see with love that little girl with a business plan under her arm?

Because that girl believed everything was possible, she didn’t weaken her plan with “buts.” She didn’t put obstacles in the way of the fortune, which she believed was waiting for her around the corner.

That girl was a believer. She believed in the miracle of multiplying bread and fish (sorry for mixing the Bible with a topic as mundane as money). She didn’t let anyone tell her that her plan to turn a dollar into salvation for her family was impossible or ridiculous.

Looking at that girl with my adult eyes, I feel (healthy) envy for the infinite naivety that moved her to believe, without limits, that she could help her family with just a dollar.

It is curious to see how our attitude towards life changes (for the worse) as we grow up. We are all born optimists. But at some point in the journey, that optimism turns into pessimism. We are born without any knowledge of the Law of Attraction. Nobody teaches us, but we apply it naturally in our actions. Let’s look at a couple of examples.

The baby cries because he knows that his mother will pick him up. Have you ever seen a baby questioning whether it is worth spending energy crying because his mother might ignore him? No. The baby cries, convinced he will get what he wants because it is his right. His conviction is proportional to the intensity of his crying. And we already know how loud a baby can cry.

The same baby grows up. As a small child, he asks his parents to read a tale every night—stories about fairies, heroes, dragons, or ferocious wolves. I don’t know any child who has interrupted the tale to question the happy ending he was listening to or to clarify that it was just a story and that real life was something else.

Let me give you another example.

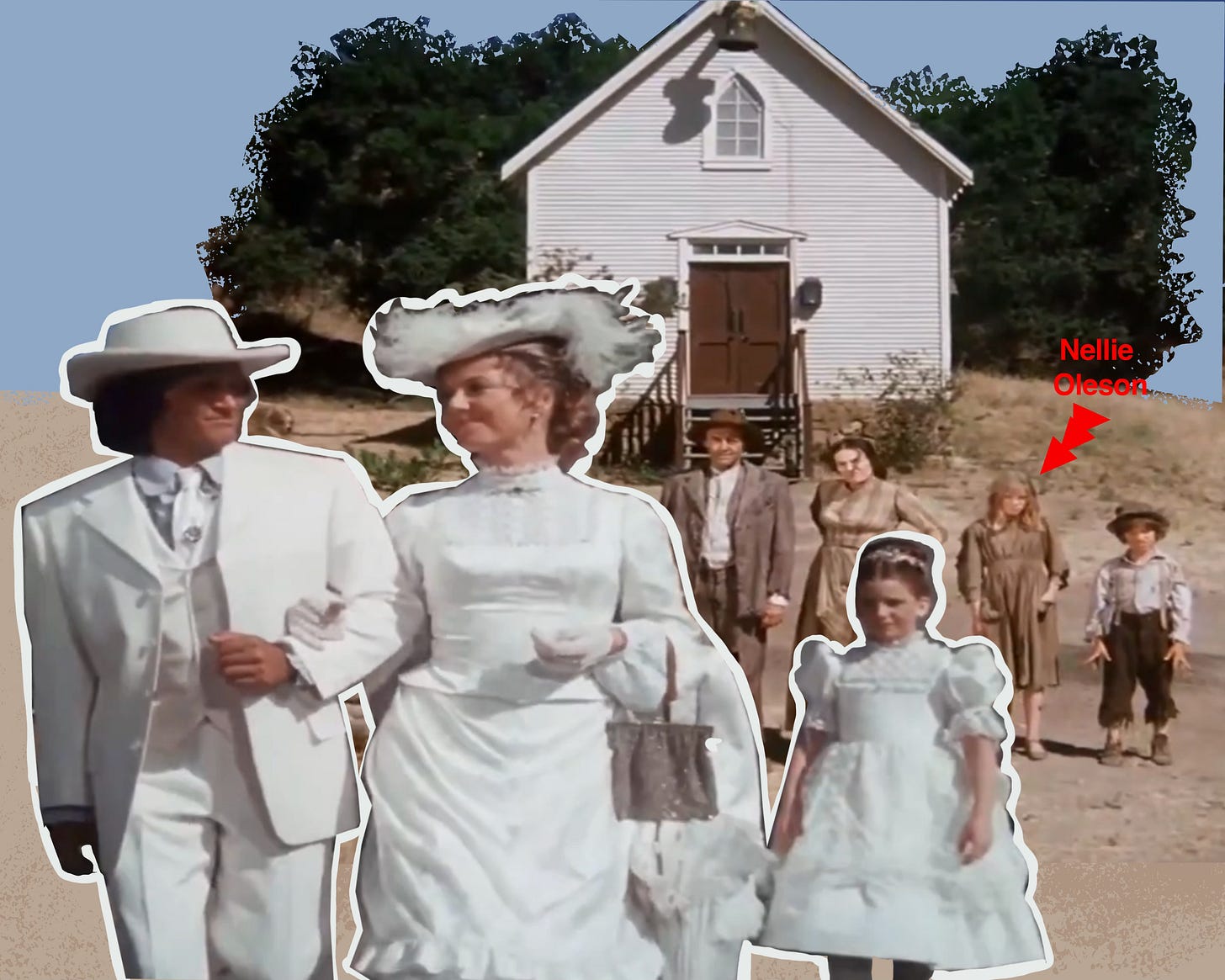

While designing my one-dollar business plan, one of my television heroines, Laura Ingalls (from the series Little House on the Prairie), faced a similar situation. I remember it well.

In Laura’s case, a twist of fate had led her to discover what seemed to be gold nuggets. Secretly, she worked hard for days to collect the precious metal that would allow her and her poor family to own the town and live in luxury.

Throughout the episode, as Laura put her heart into getting as much gold out of the creek as possible, she daydreamed about the outcome. Compared to the new life she could give the Ingallses, the comfortable life of her antagonist, the squeaky Nellie Oleson (who hasn’t dealt with one in their life?), would be nothing.

I remember eagerly watching that episode of the series. If Laura Ingalls made it big, I could too. My dollar could also lift my family out of poverty.

As I said, I don’t remember if my parents celebrated my first entrepreneurship initiative. However, I know they didn’t buy the dollar. Not remembering their reaction was probably my defence mechanism for believing I could dream big.

But Laura’s shiny nuggets were not gold, and her dreams slipped through her fingers like that glossy dust she had been taking from the water. Although her father helped her take the disappointment positively, I’m sure it left a wound in the heart of that sweet character from my childhood.

In the same way that the episode’s unfolding had exponentially increased my faith in my one-dollar business plan, the end had taught me that if I dreamed big, I could suffer.

That was the first reality check I experienced in my life. Now I understand why the school bus driver recommended my mother forbid me from watching soap operas because I spent the whole trip from home to school and back crying (I am not kidding).

The episode of Laura and the golden nuggets conveyed that dreaming was dangerous because the chances of suffering a great disappointment were very high. It was the first time I felt that dreaming was a risky enterprise, a losing gamble in which I could lose what I had invested and the faith to bet again.

Growing up, I experienced this feeling with every exam I took, every boy I liked, and every job I applied for. Every challenge I faced became a fight between my heart, which wanted to dream of the best possible outcome, and my mind, which tried to protect me from a potential frustration like the one Laura Ingalls had suffered.

So, I spent much of my life avoiding having positive expectations so that I would not suffer if my dreams were not fulfilled.

The problem is that the defence mechanism I developed didn’t prevent me from dreaming (if it had been, at least I would have lived my several decades of life in a neutral dimension). My defence mechanism consisted of visualising the worst possible outcome to create negative expectations, the ones you can use as a safety net when you fall off the trapeze (note that I say “when you fall” and not “if you fall,” to neutralise any seed of positive expectation that might grow in me).

I would generalise this personal experience to say that the problem might lie in how we relate to the gap between what we dream of and what we think we will get in response and how much we let our context define the expectations we put in our dreams.

For babies, even small children, dreaming about having all they want is as natural as breathing. It is an activity oriented towards a result that they consider guaranteed, as close at hand as the oxygen that keeps them alive.

Adopting this mindset throughout life shouldn’t be an option. It should be an obligation to ourselves. Because denying it is a luxury we cannot afford.

We cannot take half-hearted risks in the trenches of potential disappointment. We must dream big and take risks without fear that the nuggets of gold we have in our hands are just river sand. Even in the worst case, this sand will give us access to knowledge that is only accessible to those who dare to take risks.

To embrace this mindset (related to the greyhound mindset, one of the pillars of this newsletter) is to remove the barricade that the fear of suffering puts between the reality we dream of and the one we finally build. To embrace this mindset is to use certainty as a bridge between our dreams and their materialisation.

A well-known saying goes,

Necessity is the mother of invention.

All my years in survival mode have led me to rewrite this saying:

Necessity is the mother of invention, and, furthermore, it’s the sister of courage.

Thanks to the nuggets that I thought were gold but turned out to be nothing more than shiny sand, I managed to boost my creativity and build my courage. Those false nuggets gave me the strength and tools to grow internally. I gained this knowledge (a work in progress) despite my defeatist attitude.

I grew so much while suppressing my inner child and forcing myself to be pessimistic to avoid suffering. Now, imagine how much more I can grow if I let my inner child dream big and let go of the fear of not meeting the expectations that my dreams produce for me.

How ready are you to reconnect with the innocence of your inner child and let him be the one to make your requests to the universe?

Yes, so agree that meeting the needs of our inner child is the key to our abundance and success!